The Geography of Rugby in Buenos Aires: Class Inequalities through the Lens of Sports

31 January, 2018 by Sebastián Fuentes

Federico (a pseudonym) is a tall 23-year-old rugby player from Club Universitario de Buenos Aires (CUBA), located in northern Buenos Aires. He told me several times that professionalization was changing rugby, encouraging new people from the lower classes to the sport. Yet "rugby is still a posh (cheto) sport," he said, practiced by "upper-middle class families." In Buenos Aires, cheto is a contemptuous term used by non-rugby players and members of the lower classes to describe rugby players. But Federico insisted repeatedly that he was not a "typical cheto from San Isidro who thinks he is superior to any other man and woman." Like many rugby players, Federico was trying to understand the impact of rugby professionalization and globalization on the distinctions of class that rugby has helped to construct over a century. As many rugby players were talking to me about space, I came to the conclusion that rugby would be a useful lens to understand the geography of inequalities in Buenos Aires.

A municipality in Greater Buenos Aires, San Isidro is "rugby's national capital." It is one of the most emblematic locations of the upper-middle and upper classes in Buenos Aires, where four of the most important rugby clubs are located. Two of the most important in Buenos Aires are San Isidro Club (SIC) and Club Atlético de San Isidro (CASI), both with an outstanding sport performance in the local and national amateur leagues. Any citizen of Buenos Aires would recognize San Isidro as an exclusive district, even if he or she has never set foot in the municipality. Gente como uno, "people like us," is how people residing in San Isidro describe themselves, a euphemistic way to refer to their distinctions. Being como uno presupposed that one frequents rugby clubs, as well as the Jockey Club and the polo clubs, among other venues, although the clubs also include a few middle-class families. These are the institutions where families with well-known names have been gathering since the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Straight Line of Class through the Lens of Sports

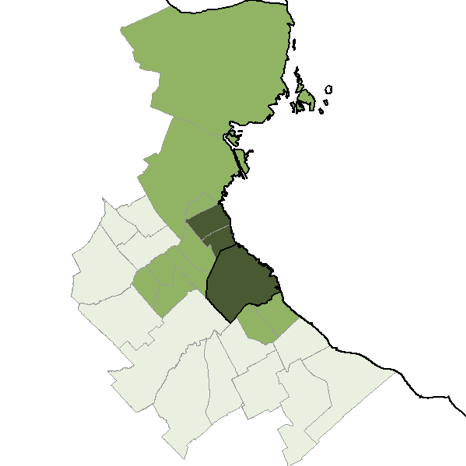

One of the more surprising aspects of the fieldwork I conducted among Buenos Aires elite rugby clubs in 2009–17 was that class is organized along a linear trajectory. Male rugby players' everyday lives, organized in terms of where they live, study, visit relatives, work, and practice sports, align along a straight line on a map (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Everyday urban path made of male elite rugby players in Buenos Aires. The thick black line shows the limits of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, surrounded by 24 municipalities that are part of the Province of Buenos Aires. (Source: edited Google Map)

Many families who are CUBA members own more than one property. A family typically lives in the gated communities in the north of Greater Buenos Aires but also owns an apartment in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ("the City"). Members of the family who are students will live in the apartment during the university year, because most universities are located downtown. Núñez, where CUBA rugby weekday training sessions are held, is halfway between the apartment and the family house.

The everyday life locations of members of the most traditional rugby clubs of the Buenos Aires Rugby Union (URBA) all fall along similar linear trajectories. The clubs that rule URBA and win most games in the amateur league are all located in the Zona Norte (Northern Zone). Being part of "the world of rugby," as they often say, is automatically associated with San Isidro (the brown bullet on Figure 1), one of the iconic places where rugby clubs have developed. San Isidro means upper-middle and upper class territory, where people actually choose to live because of the beautiful surroundings and the supposed class homogeneity.

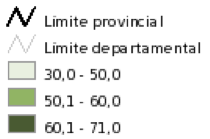

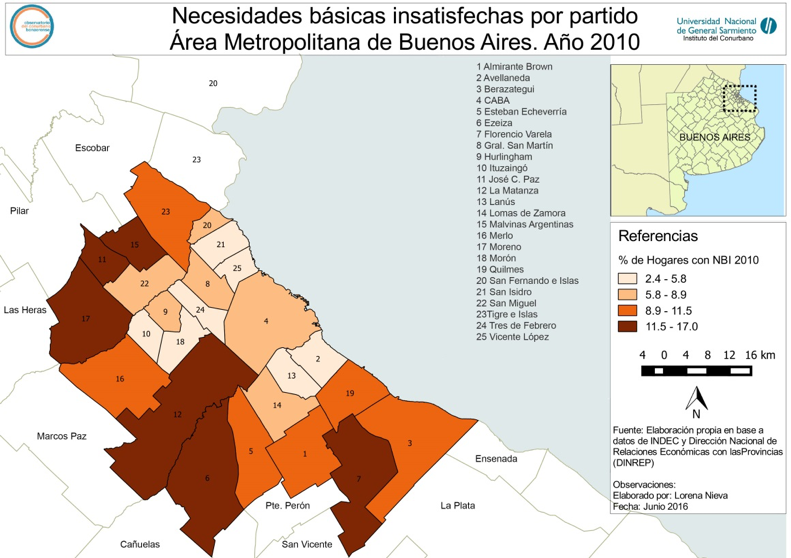

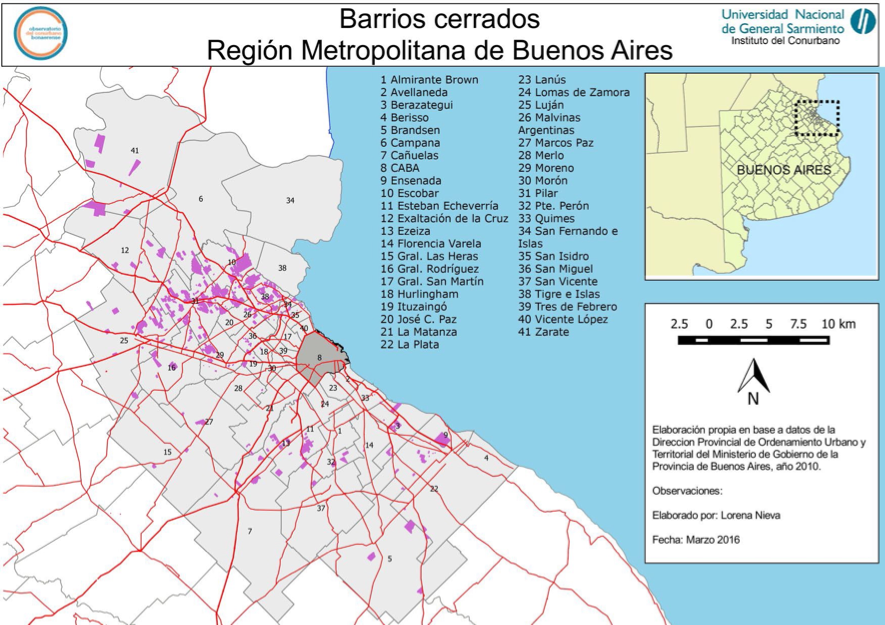

But the line on Figure 1 emerges as only a symptom of a deeply unequal urban geography when we factor in other indicators. The northern neighborhoods of the city, such as Palermo and Recoleta, and the municipalities of the Province of Buenos Aires north of the city are home to the wealthiest families, while the areas to the west and south are where the lower to middle classes live. For example, as Figure 2 demonstrates, the percentage of homes with a personal computer, a proxy index of wealth, is higher in the North than in the South or West. Similarly, distribution of homes with "unsatisfactory basic necessities" (UBN), an index based on the availability of such necessities as food, shelter, water, and clothing, etc., is highest in the south (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Percentage of homes with a personal computer in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area. (Source: National Institute of Statistics and Census, www.indec.gov.ar)

Figure 3: Percentage of homes with unsatisfied basic necessities (UBN) in Greater Buenos Aires, 2010. (Source: Observatorio del Conurbano Bonaerense, National University of General Sarmiento)

As Figure 4 demonstrates, gated communities are concentrated in the north and west of Greater Buenos Aires.

Figure 4: Gated Communities in Greater Buenos Aires, 2010. (Source: Observatorio del Conurbano Bonaerense, National University of General Sarmiento)

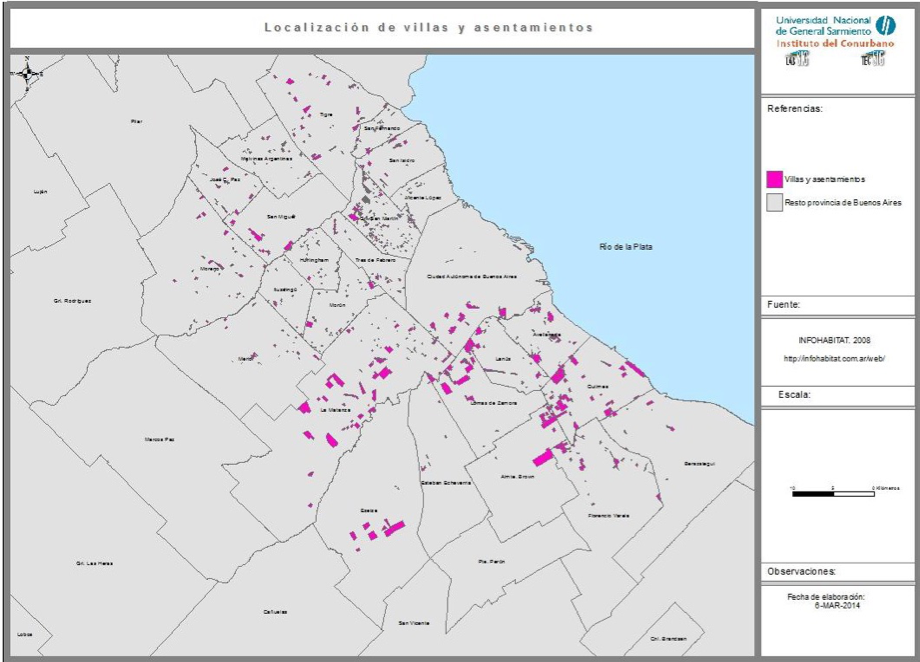

In contrast, slums (villas miseria) are concentrated in the south and west (Figure 5), even though some are also found in wealthy municipalities like San Isidro and Pilar, where they contrast starkly with the green spaces and gated communities that predominate.

Figure 5: Villas in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area, 2008. (Source: Observatorio del Conurbano Bonaerense, National University of General Sarmiento)

The image of rugby players as chetos is sustained by profound inequalities, as the geography of the city demonstrates. But class geography goes beyond demographics. Many rugby players see the wealthy district as the locations of their future lives. These are where gente como uno "naturally" belong. This sense of belonging is reinforced by the feeling that these neighbourhoods constitute the cradle of rugby, a sport they own. In contrast, soccer, Argentina's popular and a mass sport, does not have a comparable geography.

From Clubs to Civilizing the City

The spatial history of CUBA is key to understanding the association of class and space in Buenos Aires rugby. The club was created in 1918 by three groups of university students. One had lost the elections for the Students' Union of the School of Medicine at the University of Buenos Aires. The second was made up of friends who practiced sports at a local YMCA, and the third belonged to a theater group. At that time, only a few women studied at Argentinian universities, and CUBA's founders restricted its membership to men, following the model of gender-exclusive clubs in Europe. The sports the founders played at the club were the amateur sports that had globalized since the late nineteenth century with British imperial and cultural colonialism, such as boxing, soccer, and rugby.

At the time, sport was conceived as a way to foster strong bonds among young men considered "equals" in their social status. Clubs were private and selective: candidates were required to present credentials to become members, such as knowing people who were already members, and to pay a fee. The clubs were designed to prepare young men to become public men. At the club, they would not only practice sport, but also discuss politics and business. Clubs encouraged a lifestyle which encompassed amateur sports as well as cultural activities such as lectures, concerts, and plays, and the gathering of what they considered "important public men."

CUBA has since grown into a model club for men's rugby, with a formidable infrastructure. Its headquarters are located close to the Palace of Justice, and it is no coincidence that many of its members are lawyers. Two of its sport facilities are located in the fancy neighborhoods of Palermo and Núñez, and two others in the outskirts of Buenos Aires, at Villa de Mayo and Pilar. In addition, the club has two venues in the Andes: one in Bariloche and the other in Villa la Angostura, both well-known winter holiday spots for wealthy Argentinians.

One of the most important venues that CUBA member frequently talk about is the Villa de Mayo facility. At the end of the 1940s, the club bought land in that neighborhood. It intended to build new club facilities and to establish gated communities of members' weekend houses, which in Buenos Aires can be established by civic enterprises and associations such as clubs. CUBA members paid a lot of money for the land bought by the club, and the institution kept a part of the land to build sports facilities. Members always talk about the institution and familial effort to afford and build the Villa de Mayo gated community.

For example, Francisco, an important CUBA member and rugby player, whose father, brothers, and sons are all rugby players, told me that, in the sixties, his family moved from downtown to Villa de Mayo, beginning a fashion where some families established permanently. At the time, the neighborhood was a rural area without urban facilities, but Francisco's father was a kind of pioneer who could handle the disadvantages of a "virgin" place. The rural landscape had only a few houses, wild trees, and domestic animals. Francisco remembered playing rugby on those fields, running among the cows and horses. He described a landscape that, in spite of boasting a beauty unpolluted by buildings and urban problems, was also a place without the infrastructure they were accustomed to in downtown. Today, the club property at Villa de Mayo is a gated community surrounded by low-cost housing, boasting an urban infrastructure, including pavements, traffic lights, and security services.

CUBA's institutional history is filled with tales of male success, of the social recognition given to its members by Buenos Aires elite families and upper-middle-class professionals. The institutional books written by important club members showcase the members' hard work to expand the club. One of these books recounts the creation of the Núñez facility, describing how young male members, students and professionals, would clear the land to build the facilities, even working during their holidays as if they were obreros "laborers" (Club Universitario de Buenos Aires 1968, 202). Thanks to their dedication, the book continues, members transformed "a true wasteland," a "precarious zone" occupied by "low lives" into green and beautiful locations for intense sporting sociability.

The young men's efforts resemble those of obreros, even though they of course are not. But they can take on that role to transform the city and civilize space. The stories members tell help them construct a particular position, as if the city needed them. The stories construct the men as modern, moral, and civilized: they work hard to dominate nature, and they do it for the wellbeing of the city and of society, unlike ordinary obreros and other lower-class men.

Changes in Traditional Elite Spaces

The stories rugby men tell also have another purpose, in that they help them resist the changes that the configuration of rugby is undergoing on a national scale under pressure from global forces. The sport is professionalizing and this is changing its character. Today, almost all amateur matches are televised. The global corporation ESPN is one of the major sponsor or the Argentine Rugby Union (UAR), the owner of the franchise "Jaguares", the country's first professional rugby team. There is growing general interest in international matches in which the Jaguares compete with rugby teams from South Africa, New Zealand, Japan, and Australia. The sport is now reaching audiences other than upper-middle-class families. New publics attend matches held locally, and Jaguares matches are played at the Velez Sarsfield soccer club stadium and not the private amateur clubs. These changes undermine elite circles' traditional ownership of rugby and rugby is acquiring characteristics that resemble those of soccer.

As the configuration of rugby changes, some elite rugby players are creating clubs and social programs designed to "include" young people from the villas miseria, many in the Zona Norte. Club leaders describe these initiatives as "social inclusion" projects. However, they do not aim to literally "integrate" poor young people into elite clubs, but rather to create separate institutions for them, in different places, controlled by elite men. These new clubs represent an attempt to control the expansion of the sport by taking rugby to the poorest locations in the Zona Norte. While villas miseria are scattered throughout the Zona Norte, some elite men still imagine this region as socially homogeneous and elite, and act accordingly. We are still to see the consequences of these shifts on the rugby world in Buenos Aires and its spatial distinction.

Social distinctions and hierarchies, being como uno, are sustained in a geography that people build. Privileged people use the materiality of facilities, lands, and places where they move, live, recreate, and play sports to reinforce the social distinctions through and on spaces. The geography of sports can provide a useful lens to understand not only the constructed ways of being a modern and civilize man, but also the current tensions that globalization engenders, here in the form of changes in the global configuration of a particular sport, which potentially redefine local hierarchies and relations. Inquiring into spatial and geographical differences and inequalities in a growing sport such as rugby may help us understand how social transformations entailed in the way we relate and struggle for urban spaces.